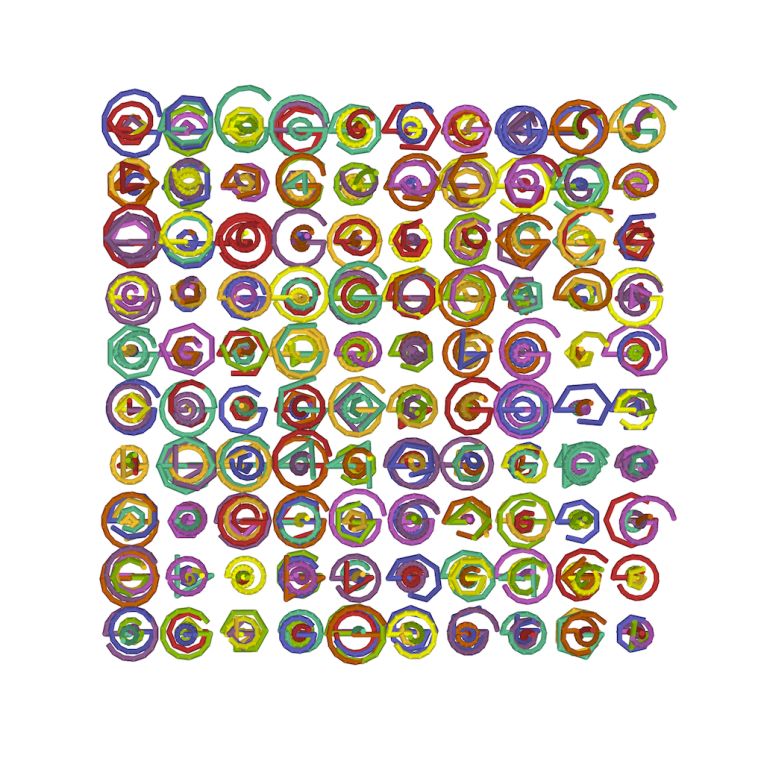

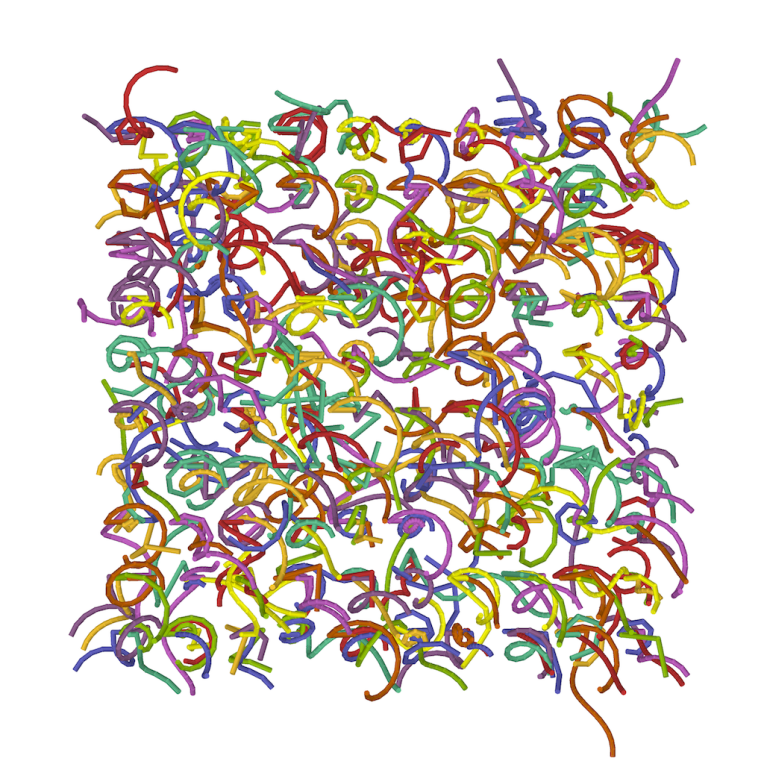

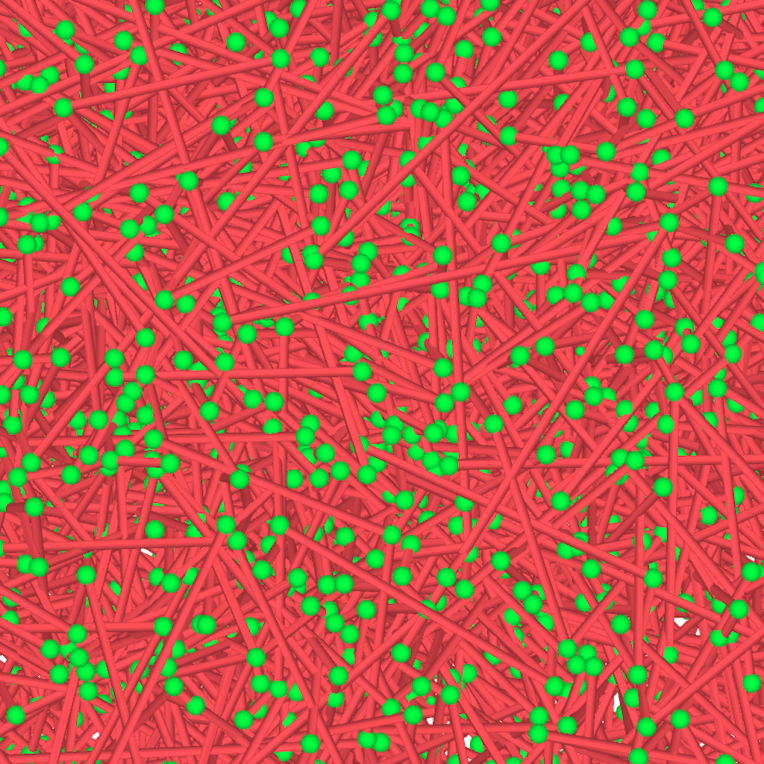

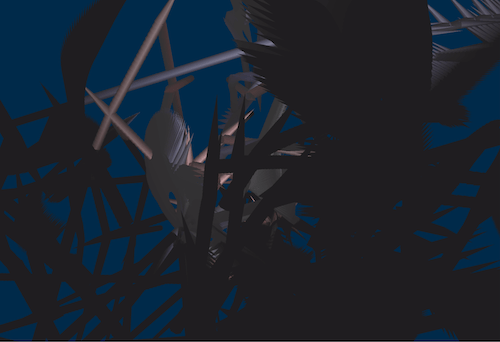

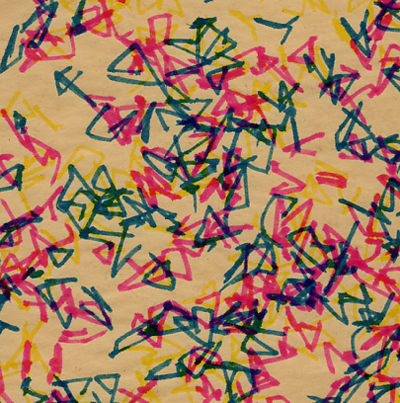

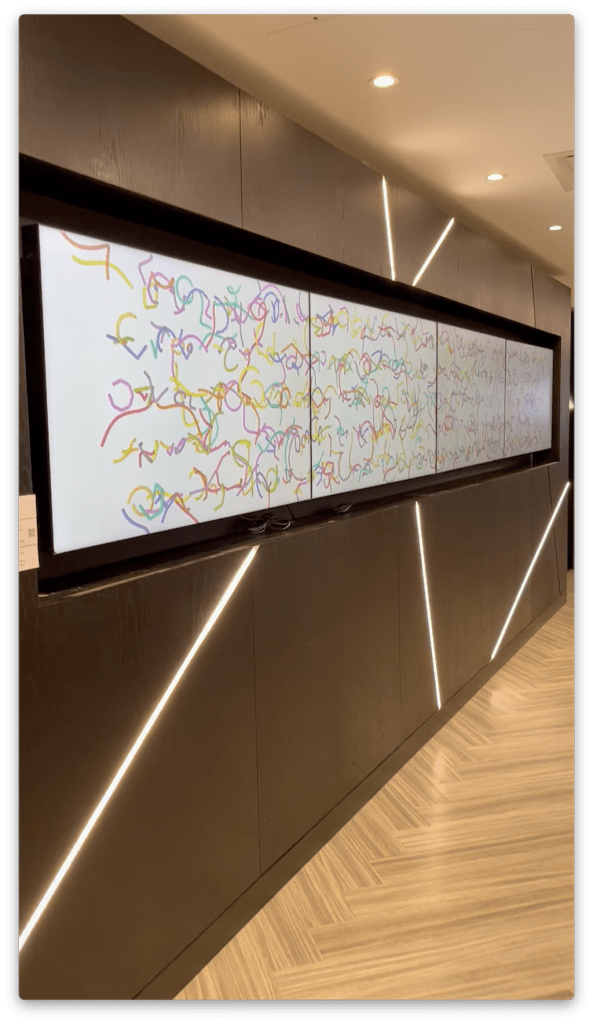

In September 2025 an exhibition of work by members of the CAS committee was installed at the London offices of the BCS in Moorgate. I had the privilege of curating the show. As a committee member I also chose to show some work. Having previously used C++ and OpenGL, for the show I used Processing for the first time to produce 3D animations to be screened as well as the images below, which were printed and framed. Two videos were formatted for the four screen video wall. There are links to view them below.

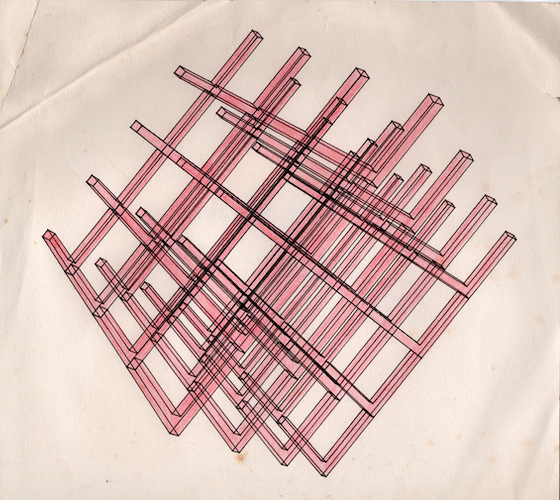

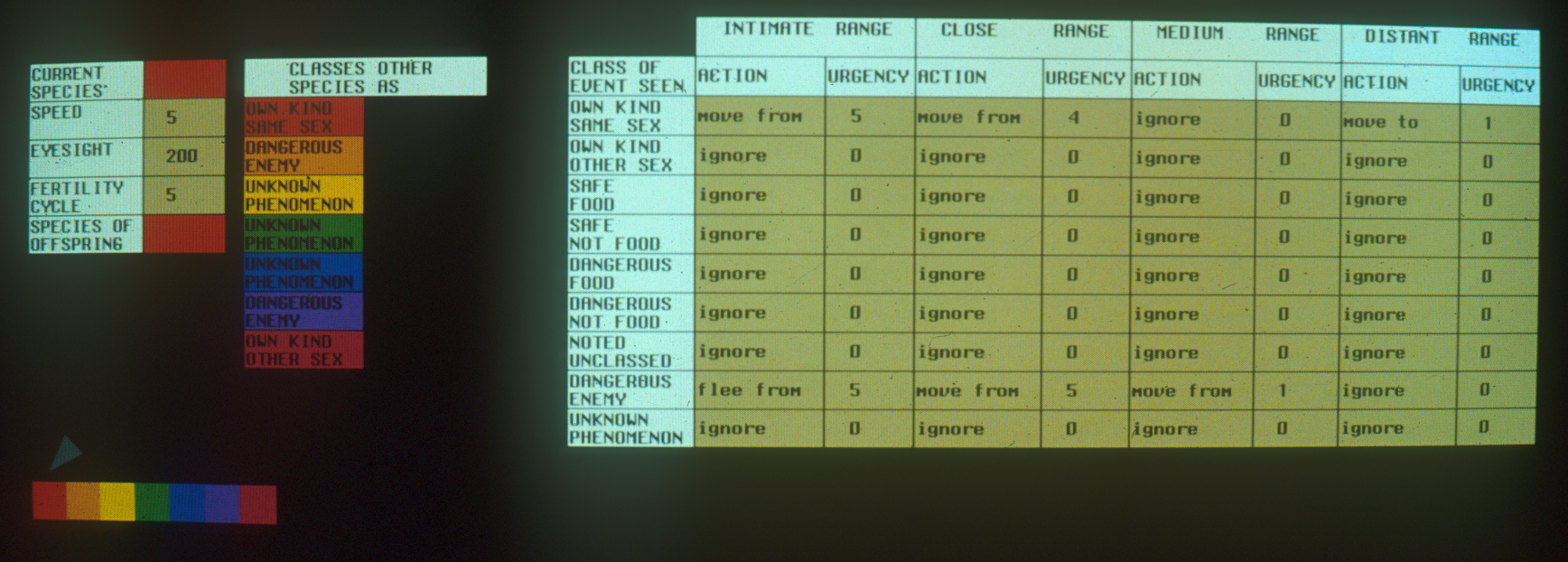

Following the example of colleagues I decided to make some new work, but related to some very old work. After a break of some fifty years, I returned to exploring the algorithms that I used back in the late nineteen-seventies first with physical sculptural constructions at Bristol Poly and then using computer graphics as a postgrad at The Slade. Back then, I used FORTRAN on a Data General Nova minicomputer. This time I used Processing on an iMac.

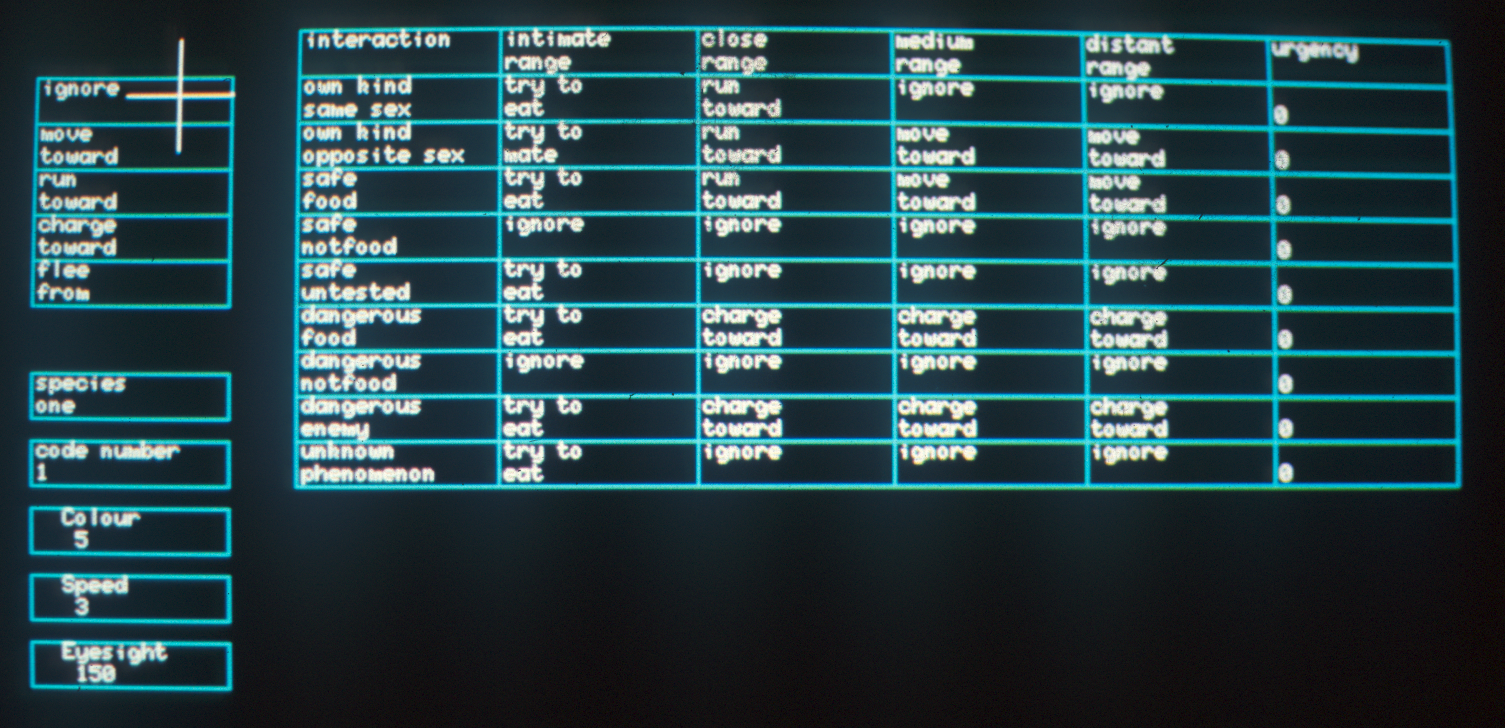

The algorithm is explained in the pages on my old website about my early computer graphics: https://stephenbell.org.uk/ranstak/index.html

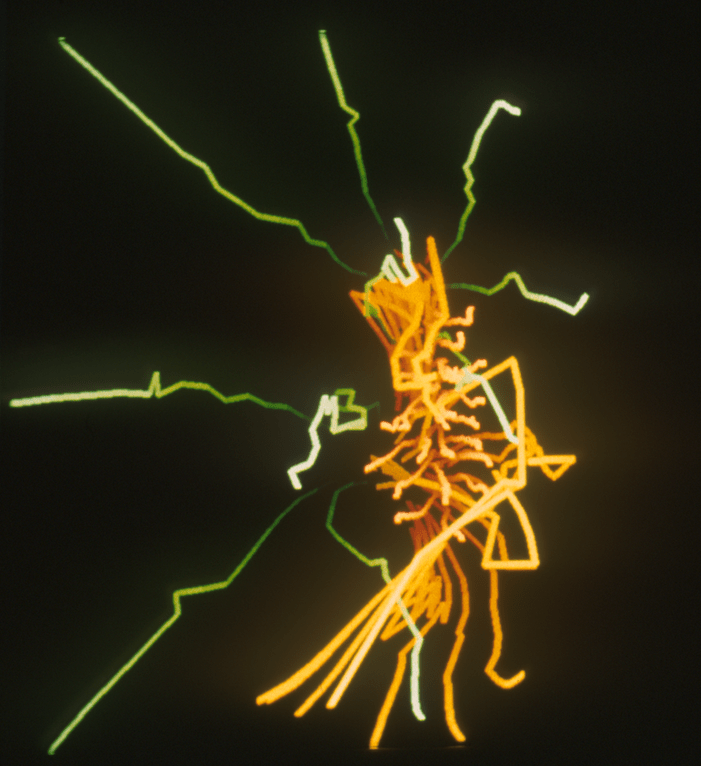

Two videos were made for the four-screen video wall at BCS Moorgate. A matrix of rotating helices of random length, frequency and amplitude provide constantly changing apparent conjunctions and combinations of shape as their overlapping forms coincide. The phases of the piece – where coloured shapes are replaced temporarily by monochrome ones and then replaced in turn by more brightly coloured helices is roughly based upon the menstrual cycle. Each video was generated using a different random number seed for the pseudo-random number generator, leading to different instances of the potential compositions.

Using Processing, which I only started learning this year, with help from the Google Gemini ‘AI’, rather than using a pen plotter the images are created using on screen rendering of the 3D geometry. A bonus of current technology compared to what I used in the 1970’s is that I can now produce animations of the shapes much more easily.